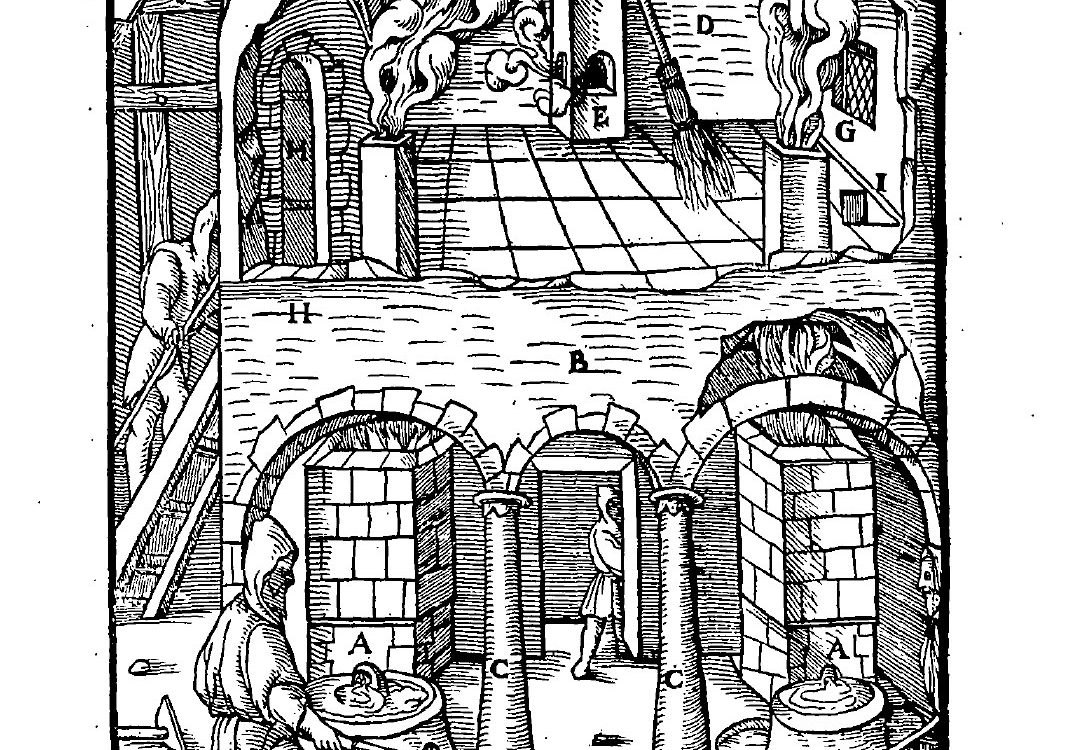

Money – the heart and engine of the capitalist process – is dirty. It always was. When Saxon polymath engineer Georg Agricola published in 1556 his much-acclaimed handbook on mining (De re metallica; the first full translation from the original Latin into modern English made by no lesser man than Herbert Hoover, later President of the United States), he was crystal clear about money’s dangerous origins:

“The critics say further that mining is a perilous occupation to pursue, because the miners are sometimes killed by the pestilential air which they breathe; sometimes their lungs rot away; sometimes the men perish by being crushed in masses of rock; sometimes, falling from the ladders into the shafts, they break their arms, legs, or necks; and it is added there is no compensation which should be thought great enough to equalize the extreme dangers to safety and life.”

Silver mining was at the heart of the capitalist transitions (and subsequent decline) that swept the German lands during the age of the early Reformation. Martin Luther’s works on economics – especially his 1524 bestseller “On Commerce and Usury” (Rössner 2015) –addressed late capitalism’s perversions that came in the wake of the last medieval mining booms that had transformed the Central German lands into silver-fuelled engines of growth. But the turbulent twenties (1520s) had also seen increasing inequality and social unrest. Skyrocketing business profits were made by late medieval super companies such as Fugger and Welser who ran some of the largest mining and smelting enterprises in the empire and practically controlled global silver flows. In numerous popular revolts that swept the German-speaking lands since the 1460s culminating in the Great German Peasant War of 1524-5 – Germany’s first revolution before 1848 – peasants complained about unduly high business profits and capitalist market manipulations. They also lamented about bad money driving out the good. This was a consequence of the global silver trades, which often left the German-speaking lands without reliable small change. What the peasants had to make do with instead were coins of dubious provenience whose value could not be asserted. These gave rise to perennial conflicts about monetary values, particularly when it came to paying taxes, tolls and other dues. Small change coins were no use for saving, either. In fact, the money of the Common Man was considered of so little value that you’d rather get rid of it as soon as you could. Very often people would only accept it at considerably discounted values, or charge a premium if they were made to accept debased coinage (Rössner 2012). Accordingly, it quickly declined in purchasing power, giving rise to inflation.