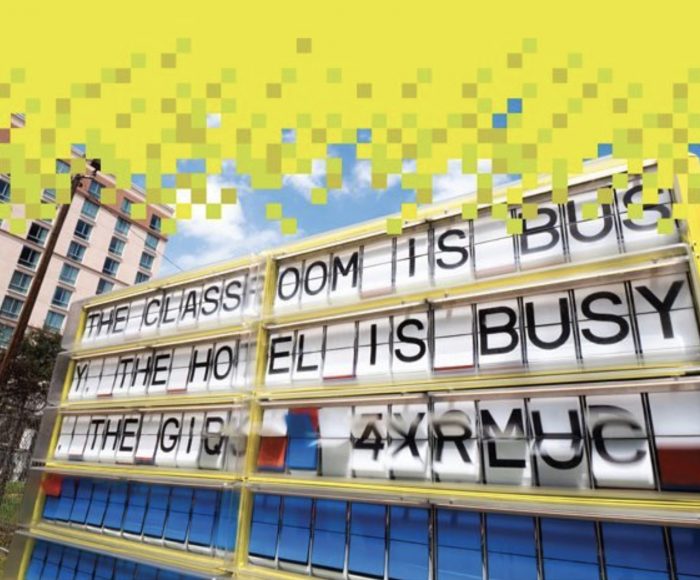

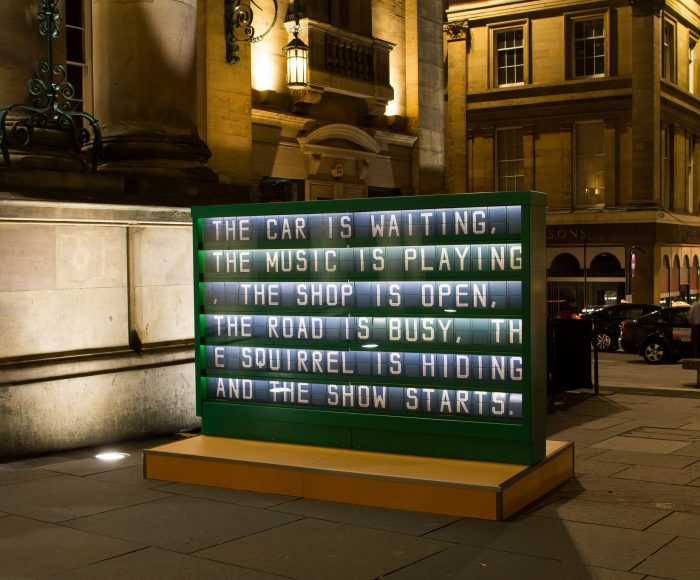

In Every Thing Every Time, a city describes itself through a narrative formatted as poems, which are based on a variety of urban data. The poems are displayed on a mechanical screen with turning letter flaps, reminiscent of old display-technologies.

Every Thing Every Time was one of three ideas that I submitted to the CityVerve public art brief, when part of Fault Lines – FutureEverything’s artist development programme. Now, two years later I’m working on the third iteration of the piece. This time it will be shown at South by Southwest (SXSW) in Austin, Texas and shortly after at Nesta Creative Economy 2019: Alternative Futures in Bristol. Each time we had finished one show, the next one was already on the horizon (I know, lucky me!), and my last two years were preoccupied with either preparing or working on a new iteration of Every Thing Every Time. The venues and size of events seem to have grown exponentially. I fluctuate between feeling stressed, a bit overwhelmed and excited, and I am constantly surprised that the idea hasn’t grown old yet.